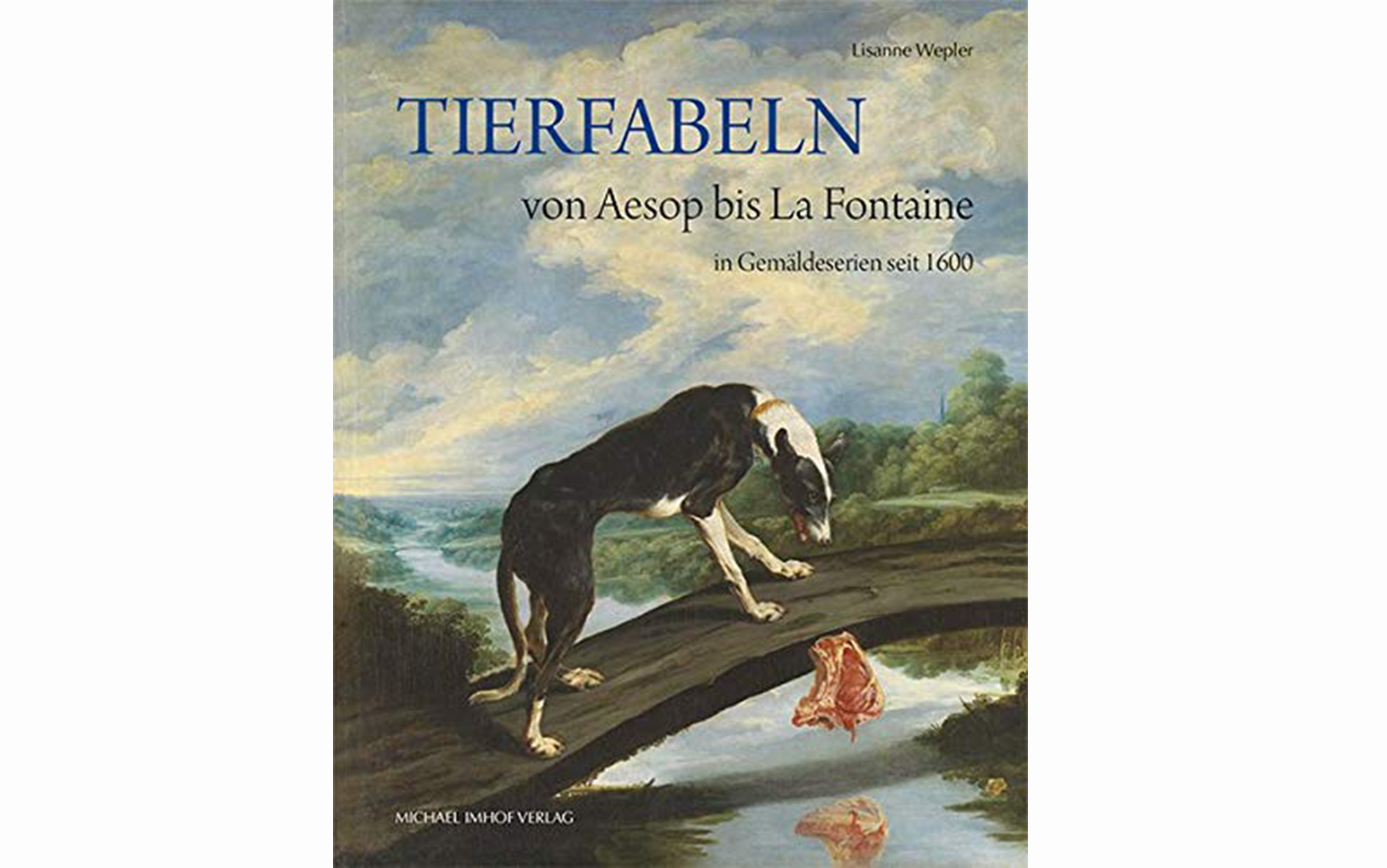

Cover

.

TIERFABELN

Von Aesop bis la Fontaine in Gemäldeserien seit 1600.

Lisanne Wepler.

Michael Imhof Verlag - 2021

Kapittel 1. AUF DEN SPUREN DER FABELTIERE

Von Aesop bis la Fontaine in Gemäldeserien seit 1600.

Lisanne Wepler.

Michael Imhof Verlag - 2021

Kapittel 1. AUF DEN SPUREN DER FABELTIERE

Page 02 - 03

.

Page 10 - 11

.

Page 12 - 13

.

Page 14 - 15

.

Page 16 - 17

.

Page 250 - 251

.

ANIMAL FABLES

From Aesop to la Fontaine in series of paintings since 1600.

Dr. Lisanne Wepler.

Chapter 1. ON THE TRAILS OF THE FABLE ANIMALS.

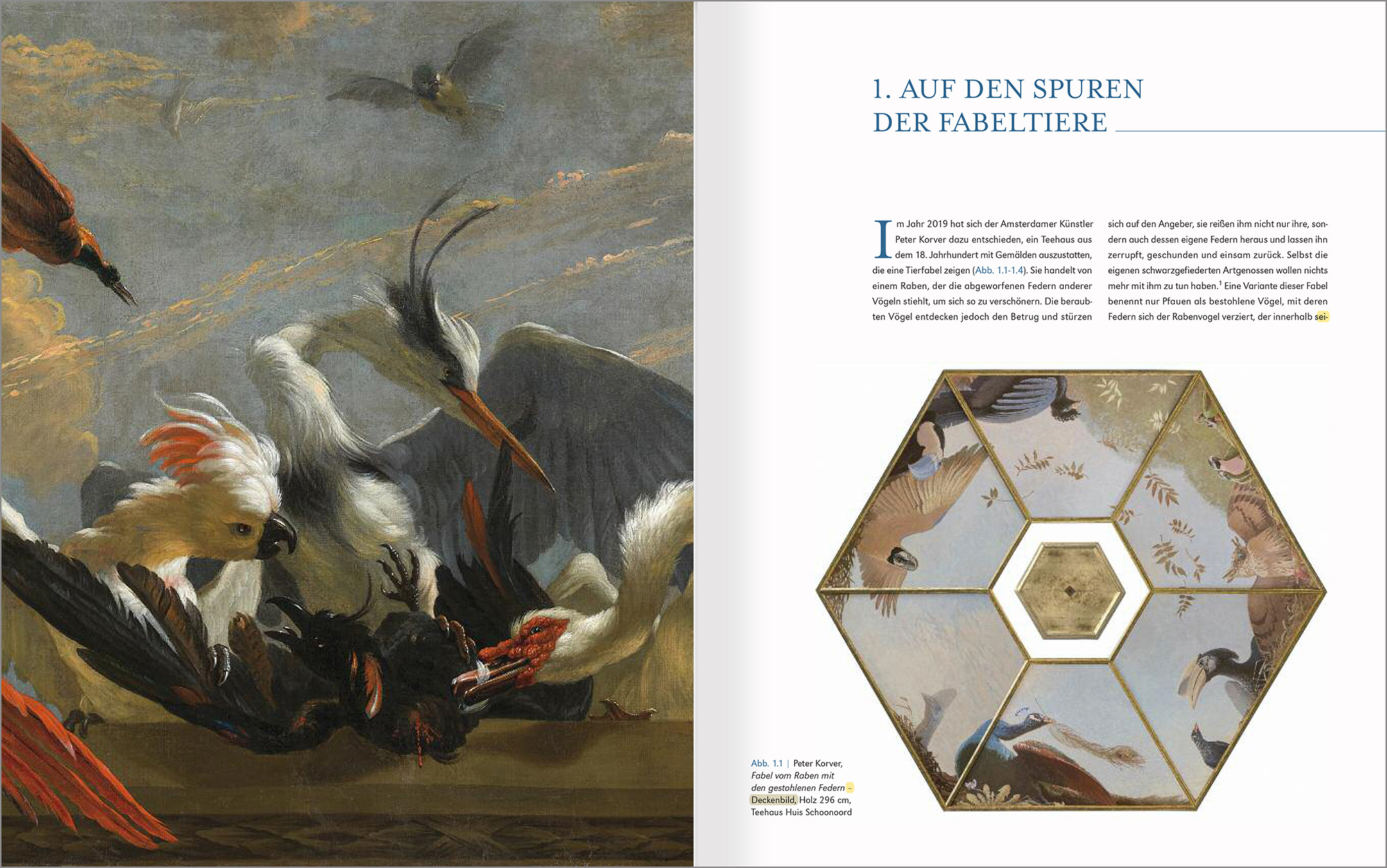

In 2018, Amsterdam artist Peter Korver decided to decorate an 18th-century tea pavilion with paintings depicting an animal fable. A story about a raven who steals other birds' dropped feathers to adorn himself. However, the robbed birds discover the fraud and pounce on the show-off, tearing out not only their feathers but also his own, leaving him torn, battered and lonely. Even their own black-feathered relatives want nothing more to do with them. A variant of this fable names only peacocks as robbed birds, with whose feathers the raven bird adorns itself, which within its biological family can also be a magpie, jackdaw, jay, crow or a raven. His goal is to mingle with their company as a disguised peacock. The proud peacocks quickly notice the stranger and snatch the stolen goods from him. The various versions boil down to a moral conclusion: one should not adorn oneself with someone else's feathers in order to gain the appreciation of others, as that way one achieves the exact opposite. Peter Korver divided the depiction of this fable into a total of four paintings; a ceiling painting and three smaller transverse rectangles to be placed over a door and two windows.

The ceiling painting is divided into six compartments corresponding to the hexagonal floor plan of the tea house and shows a total of ten different bird species. They fly against a blue sky or perch on the outer edge, creating the illusion of looking through an open roof that forms the teahouse's dome. The most prominent is the blue peacock holding one of its tail feathers in its beak. Behind him on the left a cassowary looks out, which is indicated with paler colors in aerial perspective as somewhat further away. Farther to the left, a Blue and Yellow Macaw squawks, positioning itself with outstretched wings next to a Toco Toucan with a pale blue beak and an inquisitive gaze. A Black Curassow with a perm has turned away from both. Four small parrots are sitting in the next trapeze, led by an Alexander's or Ring-necked Parakeet, which has become native to many European cities today, and three bearded parakeets next to them. To the left of the group of four, a Indian Tawny fish owl spreads its wings wide, in front of its claws are two Dutch freshwater fish: Eel and Rudd. To the left of the owl are a oriental hornbill and a Hill Myna or Beo. Macaw, Toucan and Curassow ( Hokko ) are from South America and represent for the painter Peter Korver the part of the world that was called West India in the 17th century, while the other birds all come from countries that were considered East India - today Asia.

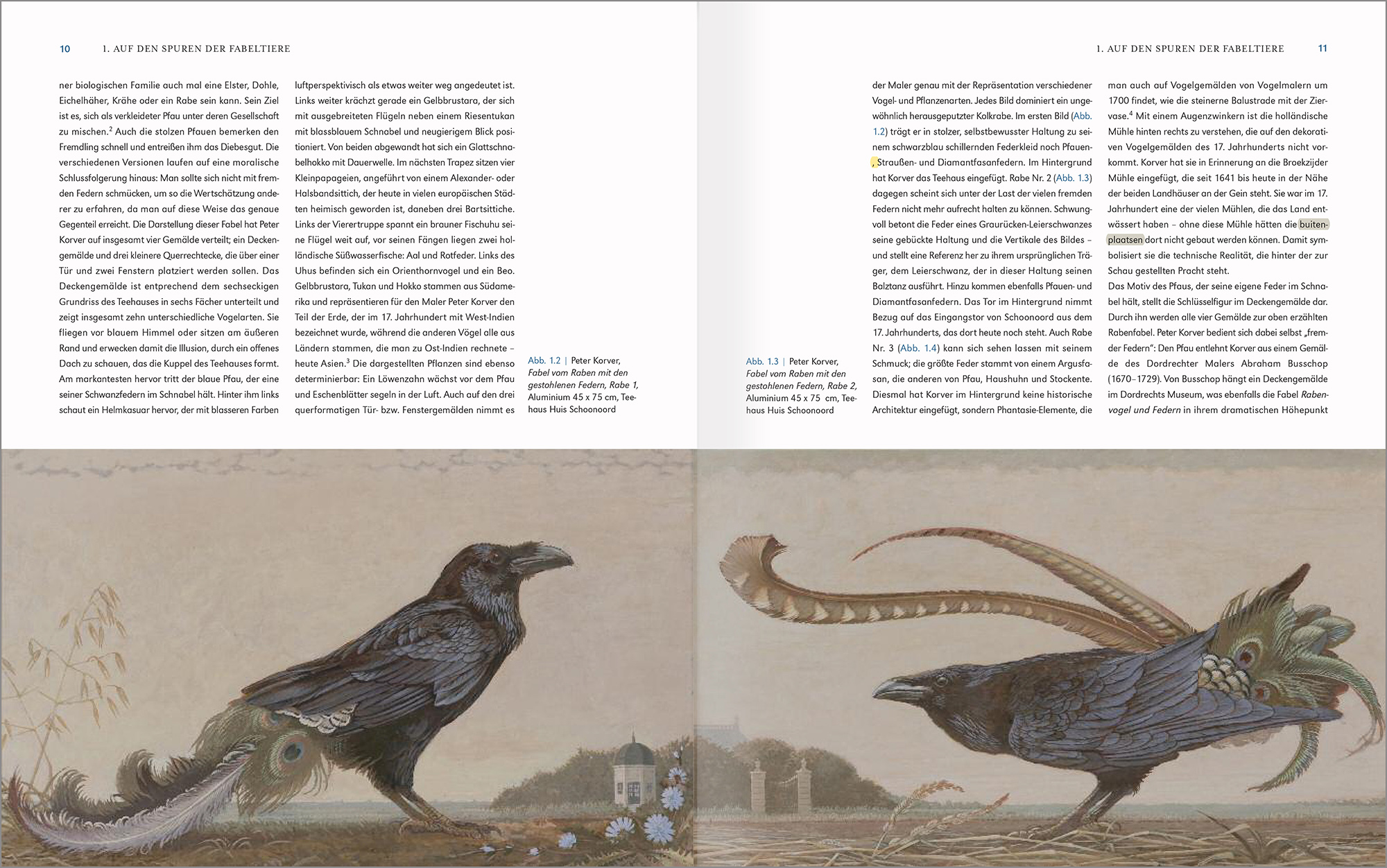

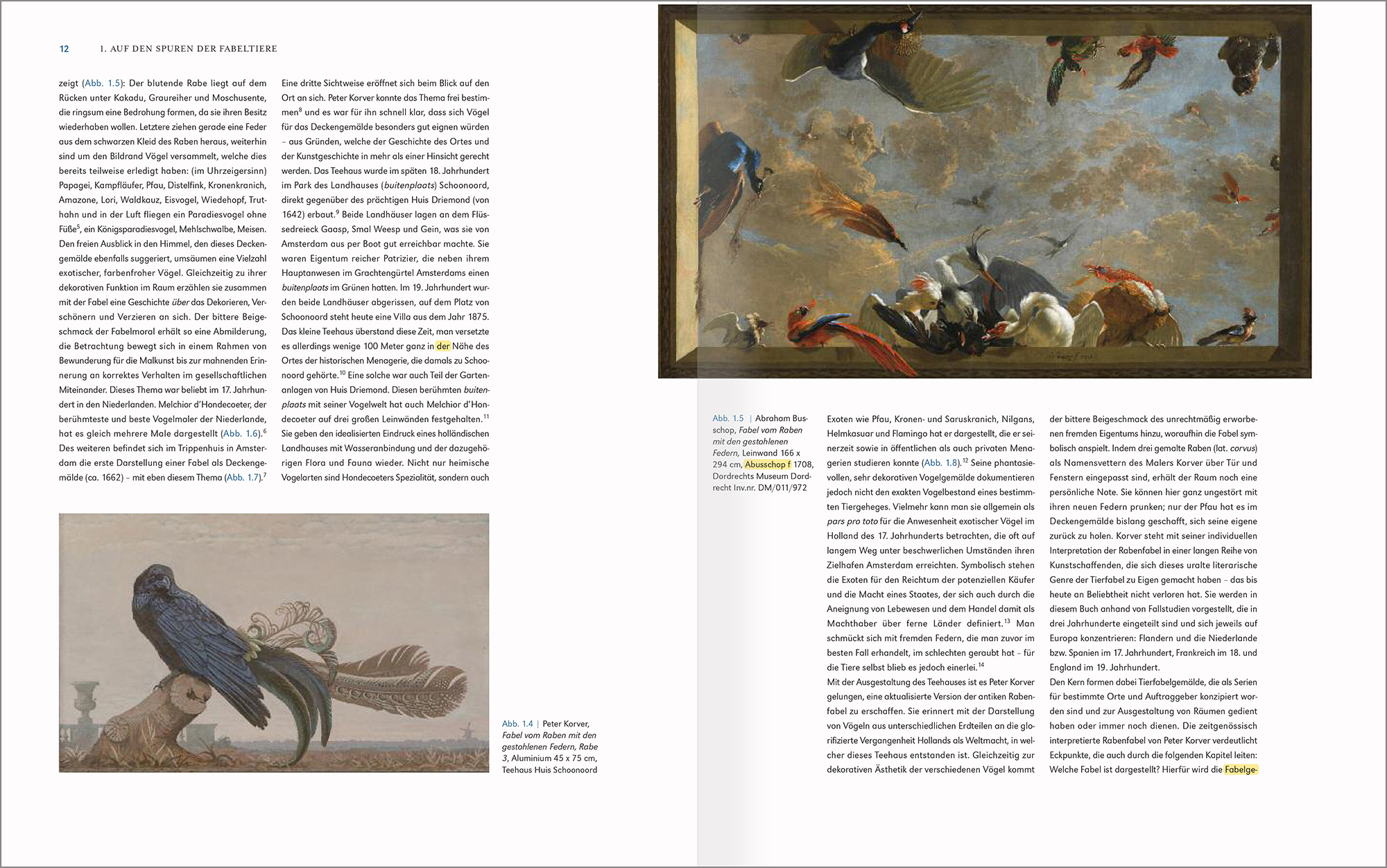

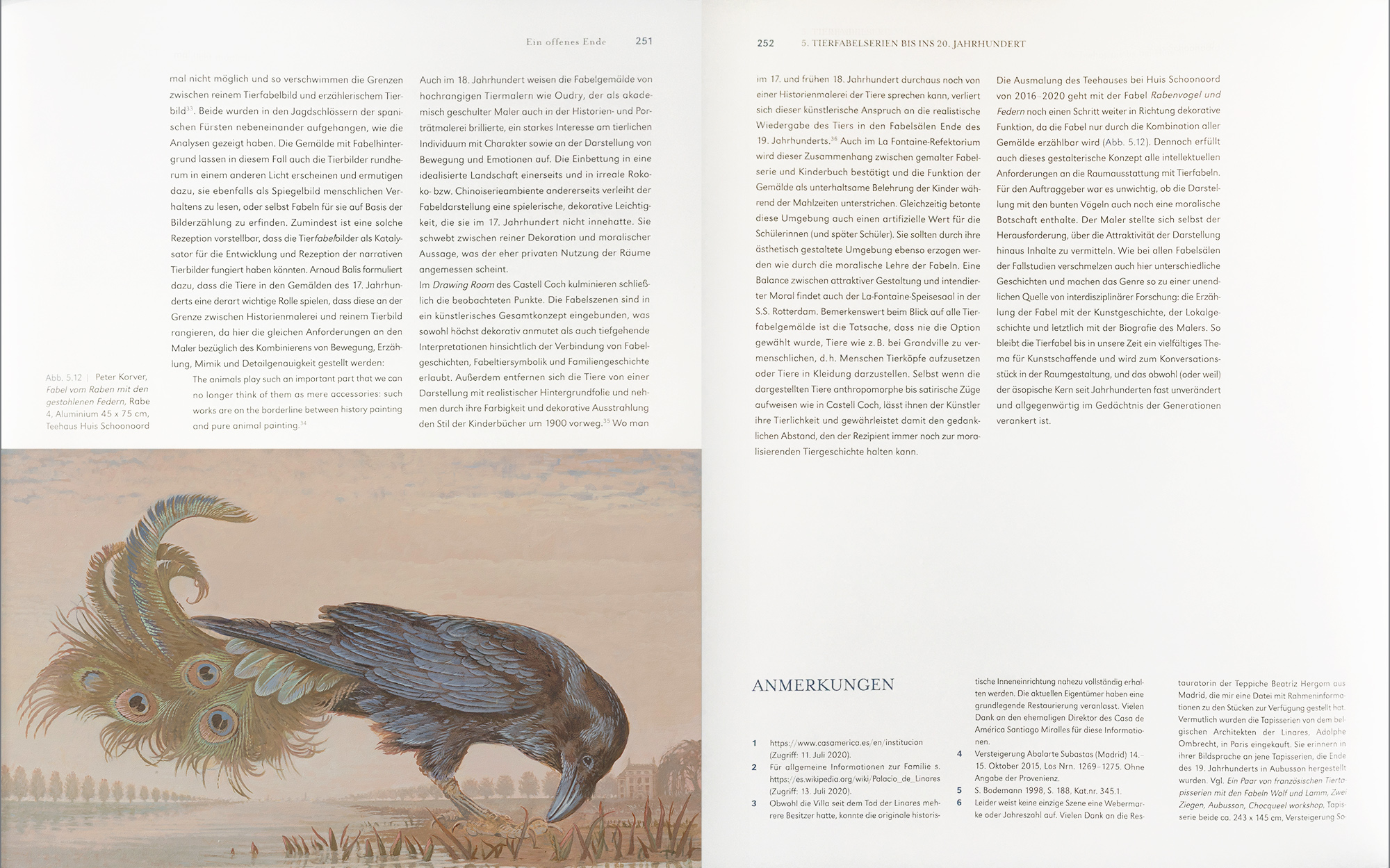

The plants depicted can also be determined: a dandelion grows in front of the peacock and ash leaves soar in the air. On the three landscape-format door and window paintings, too, the painter is meticulous about the representation of various bird and plant species. Each picture is dominated by an unusually dressed-up raven. In the first picture (Fig.) he wears peacock, ostrich and Amherst pheasant feathers in a proud, self-confident posture in addition to his iridescent blue-black plumage. Korver added the tea pavilion in the background. Raven No. 2 (Fig.), on the other hand, seems unable to stand upright under the weight of the many foreign feathers. The feather of a lyrebird energetically emphasizes its stooped posture and the verticality of the picture – and creates a reference to its original bearer, the lyrebird, who performs his courtship dance in this posture. There are also peacock and Amherst pheasant feathers. The gate in the background refers to Schoonoord's 17th-century entrance gate, which still stands there today. Raven No. 3 (Fig.) is also impressive with his ornaments; the largest feather is from an Argus pheasant, the others from peacock, domestic fowl and mallard. This time Korver has not inserted any historical architecture in the background, but rather fantasy elements that can also be found in paintings by bird painters around 1700, such as the stone balustrade with a large ornamental vase. The Dutch mill in the back right, which does not appear in the decorative bird paintings of the 17th century, is to be understood with a wink. Korver inserted it in memory of the Broekzijder Mill, which has stood near the two country houses on the Gein since 1641. In the 17th century it was one of the many mills that drained the land - without this mill the Buitenplaatsen could not have been built there. In doing so, she symbolizes the technical reality behind the magnificence on display.

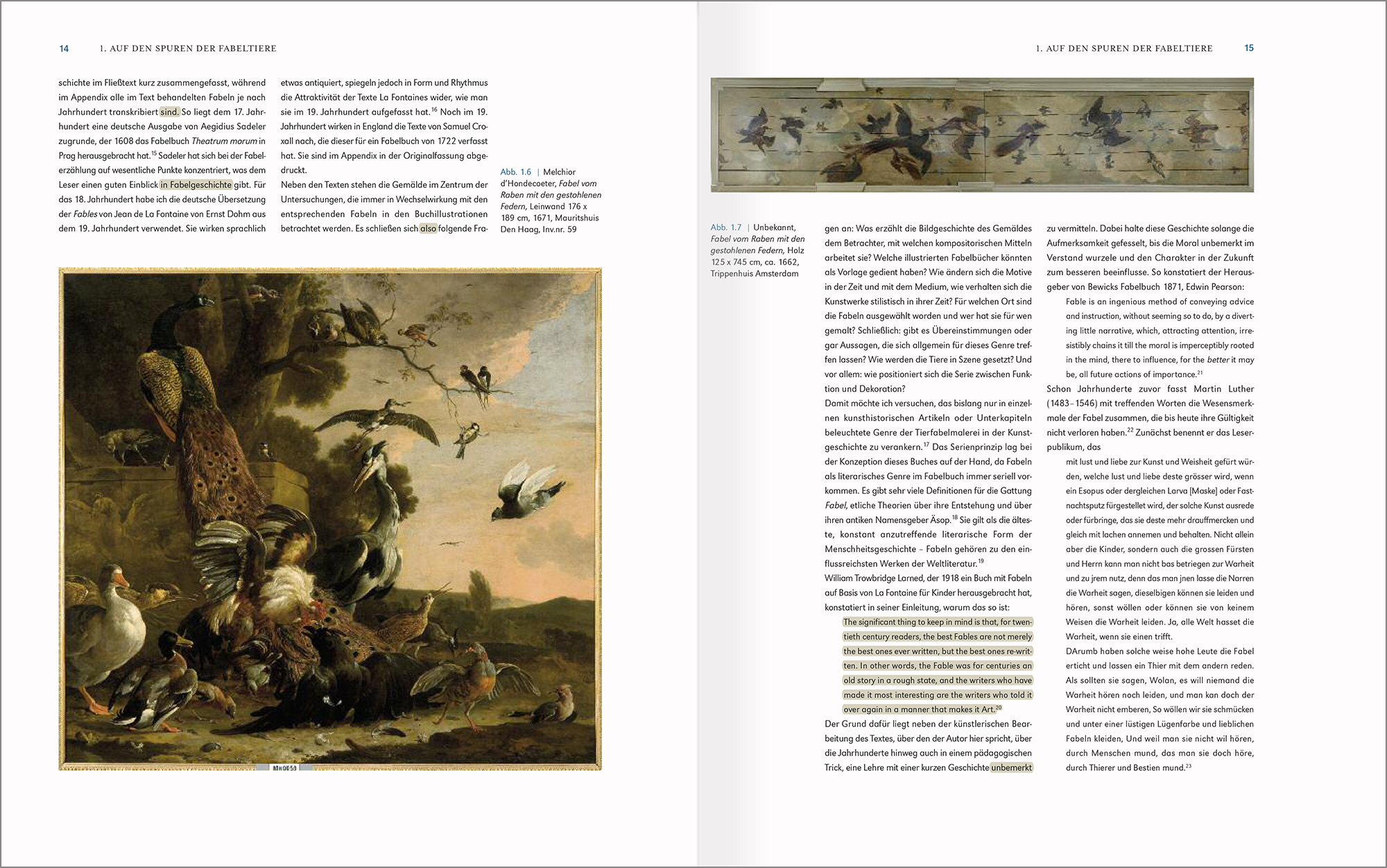

The motif of the peacock, holding its own feather in its beak, represents the key figure in the ceiling painting. Through him, all four paintings become the raven fable told above. In doing so, Peter Korver himself uses “other one’s feathers”: Korver borrowed the peacock from a painting by the Dordrecht painter Abraham Busschop (1670–1729). A ceiling painting by Busschop in the collection of the Dordrecht Museum, which also shows the fable Raven and Feathers at its dramatic climax (Fig.): The bleeding raven lies on its back under the cockatoo, gray heron and musk duck, who form a threat all around, as they are their want possession back. The latter are just pulling a feather out of the raven's black dress, birds are also gathered around the edge of the picture, some of which have already done this: (clockwise) parrot, ruff, peacock, goldfinch, crested crane, amazon, lorikeet, tawny owl, kingfisher, Hoopoe, turkey and in the air fly a bird of paradise without feet5 , a royal bird of paradise, house martin, tits. The unobstructed view of the sky, which this ceiling painting also suggests, is surrounded by a multitude of exotic, colorful birds. At the same time as their decorative function in space, they tell a story along with the fable about decorating, embellishing and embellishing in itself. The bitter aftertaste of fable morality is thus mitigated, the observation ranges from admiration for the art of painting to admonishing reminders of correct behavior in social interaction. This theme was popular in 17th-century Netherlands. Melchior d'Hondecoeter, the most famous and best painter of birds in the Netherlands, painted it several times (Fig. 1.6). 6 Furthermore, the Trippenhuis in Amsterdam contains the first depiction of a fable as a ceiling painting (ca. 1662) – with precisely this theme.

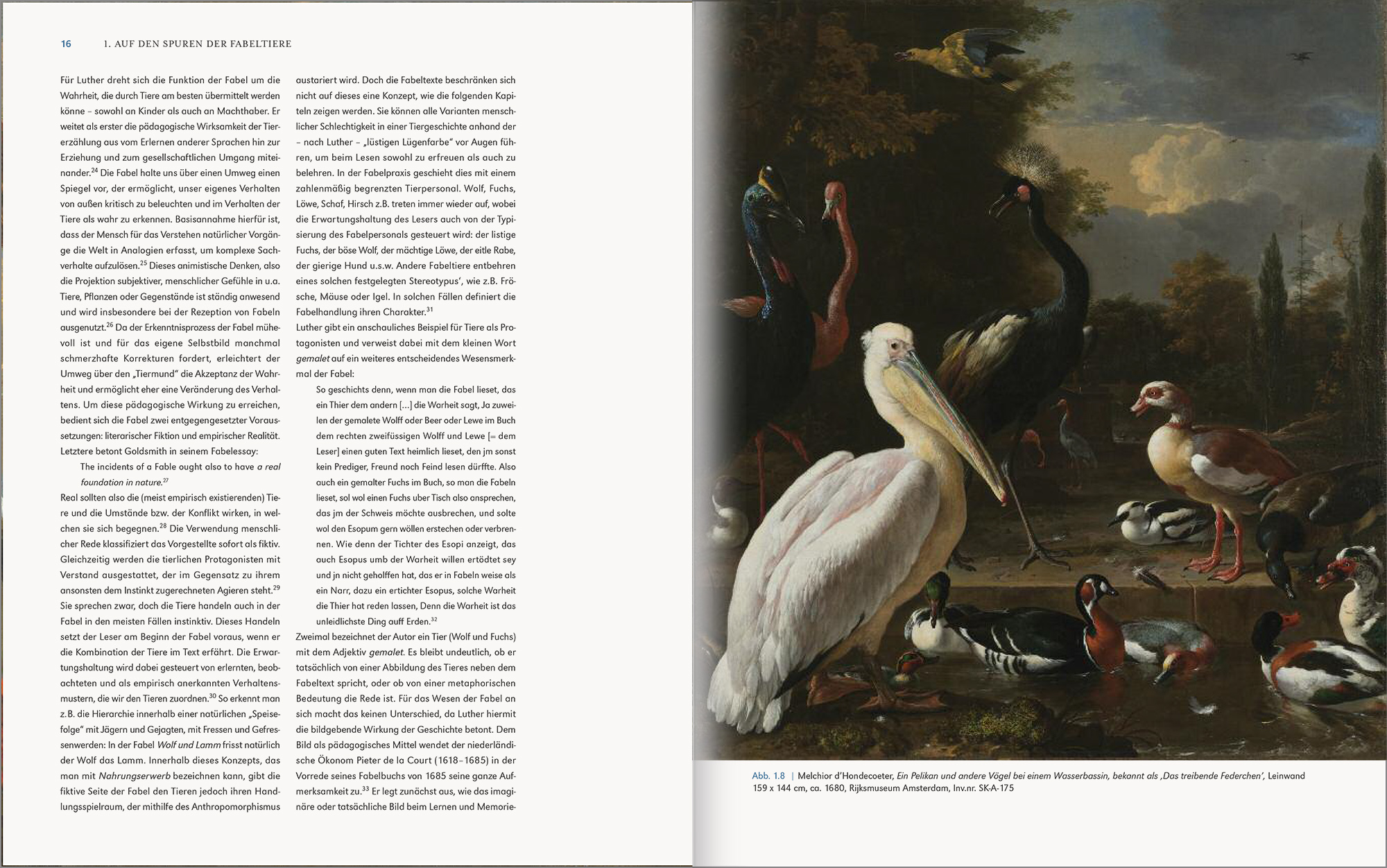

A third perspective opens up when looking at the place itself. Peter Korver was free to choose the subject8 and it quickly became clear to him that birds would be a particularly good choice for the ceiling painting – for reasons that do justice to the history of the site and art history in more ways than one. The tea house was built in the late 18th century in the park of the country house (buitenplaats) Schoonoord, directly opposite the magnificent Huis Driemond (from 1642). Both country houses were located on the river triangle Gaasp, Smal Weesp and Gein, which made them easily accessible by boat from Amsterdam. They were the property of wealthy patricians who had a buitenplaats in the countryside next to their main estate in the canal belt of Amsterdam. Both country houses were demolished in the 19th century, and a villa from 1875 now stands on Schoonoord Square Schoonoord belonged. One of these was also part of the gardens at Huis Driemond. Melchior d'Hondecoeter also captured this famous buitenplaats with its bird life on three large canvases. They give the idealized impression of a Dutch country house with a water connection and the associated flora and fauna. Not only native bird species are Hondecoeter's specialty, but he also depicted exotic ones such as peacock, crowned and sarus crane, Egyptian goose, cassowary and flamingo, which he was able to study at the time and in both public and private menageries (Fig.) However, his imaginative, highly decorative bird paintings do not document the exact number of birds in a specific animal enclosure.

Rather, they can generally be viewed as the pars pro toto for the presence of exotic birds in 17th-century Holland, which often traveled long distances and under arduous circumstances to reach their destination port of Amsterdam. The exotics symbolically stand for the wealth of potential buyers and the power of a state that defines itself as the ruler of distant lands through the appropriation of living beings and trade in them. One adorns oneself with foreign feathers, which one has previously bargained for in the best case, stolen in the bad - but for the animals themselves it was all the same. With the design of the tea house, Peter Korver has succeeded in creating an updated version of the ancient raven fable. With the depiction of birds from different continents, it reminds of the glorified past of Holland as a world power, in which this tea house was created. Simultaneously with the decorative aesthetics of the various birds, there is also the bitter aftertaste of ill-gotten property acquired by others, to which the fable alludes symbolically. Three painted ravens (lat. Corvus) as namesakes of the painter Korver are fitted above the door and windows, giving the room a personal touch. Here they can show off their new feathers undisturbed; only the peacock in the ceiling painting has so far managed to get its own back. With his individual interpretation of the raven fable, Korver stands in a long line of artists who have made this ancient literary genre of animal fables their own - which has not lost its popularity to this day. They are presented in this book through case studies divided into three centuries, each focusing on Europe: 17th-century Flanders and the Netherlands or Spain, 18th-century France and 19th-century England.The core is formed by animal fable paintings, which were conceived as a series for specific locations and clients and have served or still serve to decorate rooms. Peter Korver's contemporary interpretation of the raven fable clarifies key points that also lead us through the following chapters: . . . . . . . (page 16 )

( Page 252 )……… The paintings about the raven and the stolen feathers for the tea pavilion at Schoonoord House ( 2020 ) move another step in the direction of a decorative function, since the fable can only be read through the combination of all paintings. Nevertheless, this creative concept also fulfils all the intellectual requirements for interior design with animal fables. For the client it was of minor importance whether the embellishment with exotic birds also contained a moral message. It was the painter himself who set the challenge of conveying content beyond the attractiveness of the depiction. As with all fable rooms in this book, here too different stories merge, making the genre a never-ending source of interdisciplinary research: the narration of the fable with art history, local history and ultimately with the painter's biography. So the animal fable remains a diverse subject for artists up to our time and has become a conversation piece in interior design, even though (or because) the Aesopic core has remained almost unchanged for centuries and is ubiquitously anchored in the memory of generations.

From Aesop to la Fontaine in series of paintings since 1600.

Dr. Lisanne Wepler.

Chapter 1. ON THE TRAILS OF THE FABLE ANIMALS.

In 2018, Amsterdam artist Peter Korver decided to decorate an 18th-century tea pavilion with paintings depicting an animal fable. A story about a raven who steals other birds' dropped feathers to adorn himself. However, the robbed birds discover the fraud and pounce on the show-off, tearing out not only their feathers but also his own, leaving him torn, battered and lonely. Even their own black-feathered relatives want nothing more to do with them. A variant of this fable names only peacocks as robbed birds, with whose feathers the raven bird adorns itself, which within its biological family can also be a magpie, jackdaw, jay, crow or a raven. His goal is to mingle with their company as a disguised peacock. The proud peacocks quickly notice the stranger and snatch the stolen goods from him. The various versions boil down to a moral conclusion: one should not adorn oneself with someone else's feathers in order to gain the appreciation of others, as that way one achieves the exact opposite. Peter Korver divided the depiction of this fable into a total of four paintings; a ceiling painting and three smaller transverse rectangles to be placed over a door and two windows.

The ceiling painting is divided into six compartments corresponding to the hexagonal floor plan of the tea house and shows a total of ten different bird species. They fly against a blue sky or perch on the outer edge, creating the illusion of looking through an open roof that forms the teahouse's dome. The most prominent is the blue peacock holding one of its tail feathers in its beak. Behind him on the left a cassowary looks out, which is indicated with paler colors in aerial perspective as somewhat further away. Farther to the left, a Blue and Yellow Macaw squawks, positioning itself with outstretched wings next to a Toco Toucan with a pale blue beak and an inquisitive gaze. A Black Curassow with a perm has turned away from both. Four small parrots are sitting in the next trapeze, led by an Alexander's or Ring-necked Parakeet, which has become native to many European cities today, and three bearded parakeets next to them. To the left of the group of four, a Indian Tawny fish owl spreads its wings wide, in front of its claws are two Dutch freshwater fish: Eel and Rudd. To the left of the owl are a oriental hornbill and a Hill Myna or Beo. Macaw, Toucan and Curassow ( Hokko ) are from South America and represent for the painter Peter Korver the part of the world that was called West India in the 17th century, while the other birds all come from countries that were considered East India - today Asia.

The plants depicted can also be determined: a dandelion grows in front of the peacock and ash leaves soar in the air. On the three landscape-format door and window paintings, too, the painter is meticulous about the representation of various bird and plant species. Each picture is dominated by an unusually dressed-up raven. In the first picture (Fig.) he wears peacock, ostrich and Amherst pheasant feathers in a proud, self-confident posture in addition to his iridescent blue-black plumage. Korver added the tea pavilion in the background. Raven No. 2 (Fig.), on the other hand, seems unable to stand upright under the weight of the many foreign feathers. The feather of a lyrebird energetically emphasizes its stooped posture and the verticality of the picture – and creates a reference to its original bearer, the lyrebird, who performs his courtship dance in this posture. There are also peacock and Amherst pheasant feathers. The gate in the background refers to Schoonoord's 17th-century entrance gate, which still stands there today. Raven No. 3 (Fig.) is also impressive with his ornaments; the largest feather is from an Argus pheasant, the others from peacock, domestic fowl and mallard. This time Korver has not inserted any historical architecture in the background, but rather fantasy elements that can also be found in paintings by bird painters around 1700, such as the stone balustrade with a large ornamental vase. The Dutch mill in the back right, which does not appear in the decorative bird paintings of the 17th century, is to be understood with a wink. Korver inserted it in memory of the Broekzijder Mill, which has stood near the two country houses on the Gein since 1641. In the 17th century it was one of the many mills that drained the land - without this mill the Buitenplaatsen could not have been built there. In doing so, she symbolizes the technical reality behind the magnificence on display.

The motif of the peacock, holding its own feather in its beak, represents the key figure in the ceiling painting. Through him, all four paintings become the raven fable told above. In doing so, Peter Korver himself uses “other one’s feathers”: Korver borrowed the peacock from a painting by the Dordrecht painter Abraham Busschop (1670–1729). A ceiling painting by Busschop in the collection of the Dordrecht Museum, which also shows the fable Raven and Feathers at its dramatic climax (Fig.): The bleeding raven lies on its back under the cockatoo, gray heron and musk duck, who form a threat all around, as they are their want possession back. The latter are just pulling a feather out of the raven's black dress, birds are also gathered around the edge of the picture, some of which have already done this: (clockwise) parrot, ruff, peacock, goldfinch, crested crane, amazon, lorikeet, tawny owl, kingfisher, Hoopoe, turkey and in the air fly a bird of paradise without feet5 , a royal bird of paradise, house martin, tits. The unobstructed view of the sky, which this ceiling painting also suggests, is surrounded by a multitude of exotic, colorful birds. At the same time as their decorative function in space, they tell a story along with the fable about decorating, embellishing and embellishing in itself. The bitter aftertaste of fable morality is thus mitigated, the observation ranges from admiration for the art of painting to admonishing reminders of correct behavior in social interaction. This theme was popular in 17th-century Netherlands. Melchior d'Hondecoeter, the most famous and best painter of birds in the Netherlands, painted it several times (Fig. 1.6). 6 Furthermore, the Trippenhuis in Amsterdam contains the first depiction of a fable as a ceiling painting (ca. 1662) – with precisely this theme.

A third perspective opens up when looking at the place itself. Peter Korver was free to choose the subject8 and it quickly became clear to him that birds would be a particularly good choice for the ceiling painting – for reasons that do justice to the history of the site and art history in more ways than one. The tea house was built in the late 18th century in the park of the country house (buitenplaats) Schoonoord, directly opposite the magnificent Huis Driemond (from 1642). Both country houses were located on the river triangle Gaasp, Smal Weesp and Gein, which made them easily accessible by boat from Amsterdam. They were the property of wealthy patricians who had a buitenplaats in the countryside next to their main estate in the canal belt of Amsterdam. Both country houses were demolished in the 19th century, and a villa from 1875 now stands on Schoonoord Square Schoonoord belonged. One of these was also part of the gardens at Huis Driemond. Melchior d'Hondecoeter also captured this famous buitenplaats with its bird life on three large canvases. They give the idealized impression of a Dutch country house with a water connection and the associated flora and fauna. Not only native bird species are Hondecoeter's specialty, but he also depicted exotic ones such as peacock, crowned and sarus crane, Egyptian goose, cassowary and flamingo, which he was able to study at the time and in both public and private menageries (Fig.) However, his imaginative, highly decorative bird paintings do not document the exact number of birds in a specific animal enclosure.

Rather, they can generally be viewed as the pars pro toto for the presence of exotic birds in 17th-century Holland, which often traveled long distances and under arduous circumstances to reach their destination port of Amsterdam. The exotics symbolically stand for the wealth of potential buyers and the power of a state that defines itself as the ruler of distant lands through the appropriation of living beings and trade in them. One adorns oneself with foreign feathers, which one has previously bargained for in the best case, stolen in the bad - but for the animals themselves it was all the same. With the design of the tea house, Peter Korver has succeeded in creating an updated version of the ancient raven fable. With the depiction of birds from different continents, it reminds of the glorified past of Holland as a world power, in which this tea house was created. Simultaneously with the decorative aesthetics of the various birds, there is also the bitter aftertaste of ill-gotten property acquired by others, to which the fable alludes symbolically. Three painted ravens (lat. Corvus) as namesakes of the painter Korver are fitted above the door and windows, giving the room a personal touch. Here they can show off their new feathers undisturbed; only the peacock in the ceiling painting has so far managed to get its own back. With his individual interpretation of the raven fable, Korver stands in a long line of artists who have made this ancient literary genre of animal fables their own - which has not lost its popularity to this day. They are presented in this book through case studies divided into three centuries, each focusing on Europe: 17th-century Flanders and the Netherlands or Spain, 18th-century France and 19th-century England.The core is formed by animal fable paintings, which were conceived as a series for specific locations and clients and have served or still serve to decorate rooms. Peter Korver's contemporary interpretation of the raven fable clarifies key points that also lead us through the following chapters: . . . . . . . (page 16 )

( Page 252 )……… The paintings about the raven and the stolen feathers for the tea pavilion at Schoonoord House ( 2020 ) move another step in the direction of a decorative function, since the fable can only be read through the combination of all paintings. Nevertheless, this creative concept also fulfils all the intellectual requirements for interior design with animal fables. For the client it was of minor importance whether the embellishment with exotic birds also contained a moral message. It was the painter himself who set the challenge of conveying content beyond the attractiveness of the depiction. As with all fable rooms in this book, here too different stories merge, making the genre a never-ending source of interdisciplinary research: the narration of the fable with art history, local history and ultimately with the painter's biography. So the animal fable remains a diverse subject for artists up to our time and has become a conversation piece in interior design, even though (or because) the Aesopic core has remained almost unchanged for centuries and is ubiquitously anchored in the memory of generations.