New Paintings for the entrance of a 1790's Amsterdam monument

.

.

New Paintings for the entrance of a 1790's Amsterdam monument

Since spring 2012 a 1790’s palazzo on an Amsterdam canal houses a new series of paintings by Peter Korver. The art works were commissioned by its present owners who, along with their guests, now enjoy the luxury of a permanent private viewing.

An image of support-acts

Korver has not only depicted Lebrun, Napoleons remplaçant in the Netherlands, in the hall of Herengracht 40, but also the Emperors brother Louis, King of Holland from 1806 until 1810, and Bonaparte’s son, a baby baptized “King of Rome”. With Lebrun depicted in a triptych and the other two in a single painting, Napoleon is clearly the link between the three explicitly left out. The decision to use “the son”, “the brother” and “the friend” only, gave us a much more exiting image in the end; a surrounding image of “supporting acts” ’, Korver says.

Painting in the entrance of Herengracht 40, with a portrait of Charles François LeBrun,

Napoleons Gouverneur presiding over the Netherlands from this adress.

Photo: Eddy Wenting

.

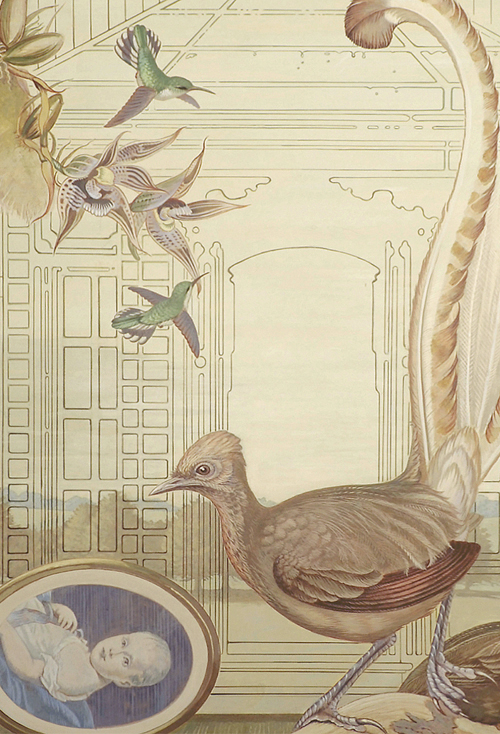

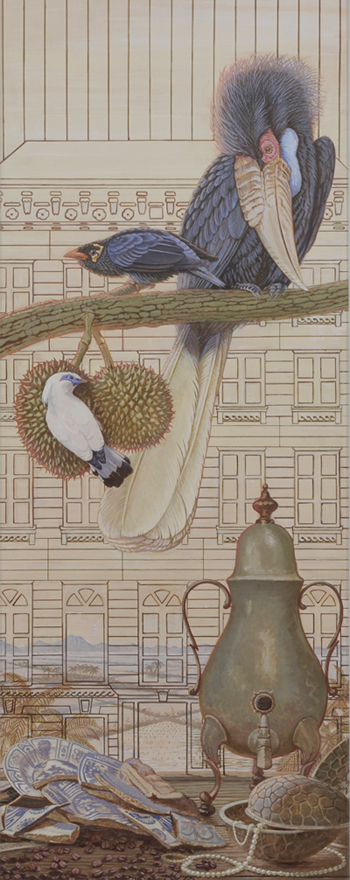

Detail of Histoire Naturelle III, one of the panels in the entrance of Herengracht 40.

Tempera and acrylic on Aluminium panel.

.

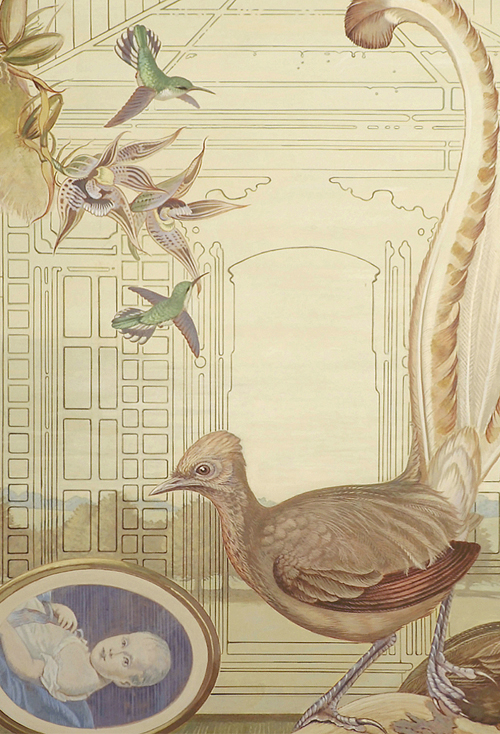

Detail with Lyrebird and portrait of Roi de Rome, Bonapartes only child.

Tempera and acrylic on Aluminium panel.

Aviaries with doors wide open

Apart from two portrait-medallions lying around like eggs on the floor, the bust of Louis and some other historic memorabilia, more than forty birds primarily dominate the foreground of these Trompe-l’oeil paintings. In the background a pattern of lines and ornaments emerges, taken from 18th century architectural drawings and representing the delicate bars of a cage. A cage, however, with its doors wide open; the birds appear to stay inside voluntarily. They seem preoccupied with all sorts of activities but in the end there is nothing keeping them from stepping out and flying away into the open landscape that stretches out beyond the bars. Korver is clear about the analogy: ‘I liked this as an image in relation to the French Revolution, the Dutch 18th century patriot movement, the whole French period in this country and the ambivalent attitude that people in general appear to have towards the idea of freedom. ‘The Spanish director Louis Buñuel once started his film Le Fantôme de la Liberté with a reference to the story of Spanish rebels during the Napoleonic occupation, dying before the firing squad, cheering “down with liberty”. Of course there is a lot more to say about what kind of liberté the French were really bringing to Spain in those days, but as an image of a radically denounced freedom, it is a very intriguing story.’

Painting in the entrance of Herengracht 40, featuring Bonapartes brother Louis, King of Holland 1806 -1819.

Tempera and acrylic on Aluminium panel.

.

In the background of these paintings, the bars of the cages refer to a popular tradition in Dutch 18th and 19th century interior decoration: fashionable painted wall hangings and panelled boiseries with scenic views of the river Vecht, a meandering stream connecting Amsterdam to the nearby city of Utrecht. On the second floor of this house, a room with eight such paintings has survived to the present day. Another of those series, once illuminating the large hall in the back of the main house is now part of the Amsterdam Historic Museum collection. For Amsterdam’s 18th century merchant nobility a countryside mansion on the banks of this, or any of the other romantic rivers around the city, was a “must have”. In light of this tradition Korver took drawings of the dome shaped teahouses that were a standard garden accessory of these leisurely dwellings, and transformed them into a gallery of aviaries. A collection of birds in 18th century fashion, from the time when human knowledge was to be ordered, preferably in that most popular product of French Enlightenment: the Encyclopedie. ‘Most of these teahouses have a certain birdcage shape by nature’, Korver says. ‘ This turned out to be a nice advantage in the process.’

With the birds, Korver places his paintings in another tradition as well: the 17th century genre of birdpaintings of the likes by Melchior de Hondecoeter, Jan Fyt, Marghareta de Heer en Frans Snyders. These depicted courtyards of mansions or farms, gardens and menageries with groups of exotic birds or domestic fowl. ‘Paintings like these often had a hidden message. Especially the “concert of the birds” paintings and the so-called “mocking of the owl” genre can be regarded as commenting on the politics of the day.’The way these birds are painted however, recall the hand coloured copper engravings of a later date, the Natural Historic encyclopaedias of Buffon /the Seve, Cornelius Nozeman, William Jardine, Jacques Barraband or James Audubon. In this way the paintings at Herengracht 40 are anachronistically embedded in several traditions and styles simultaneously, and so by their very nature blend in elegantly in a house that finds its origin in a period which can rightfully be called a turning point in History.

A second Chapter

Shortly after the first three paintings had been installed in the entrance, the owners approached Korver again. They thought the large space in the back of the hall a perfect option for a continuation of this painted history. ‘After a short period of research and discussion, we all agreed that the large fourth painting would be of Amsterdam city hall. It had once been the world’s largest secular building, a palace for 17th century civil democracy; in 1806 it was redecorated into the Royal Palace for Napoleons brother, and after some years of service as administrative palace for Gouverneur LeBrun, it was donated as Royal Palace to the returning Prince of Orange in 1813. While France over the years managed to transform itself from monarchy into a republic, the Netherlands had done just the opposite.’ A smaller fifth and last painting was to depict the subject of the Nederlandsche Handel Maatschappij (NHM), a company founded by the new king William I of Orange, which would turn Herengracht 40 into its head office some years later. For several decades it would manage the colonial exploitation of today’s Indonesia from this address.

Painting in the entrance of Herengracht 40, with the outline of Amsterdam City Hall.

1813 being the year it was transformed into a seldomly used Royal Palace.

.

Hôtel de Ville 1813 - ( City Hall 1813 ) is a large triptych painting about the return of the house of Orange and features the front of Amsterdam’s former city hall, wide open like a theatre stage, displaying a panoramic view of a maritime landscape. The foreground is crowded with marine birds flapping their wet feet over a wooden floor, on a wave of old mattresses and around furniture left by former inhabitants. An 18th century copper engraving hangs from the bars like a pamphlet showing an Orange Cock of the Rocks. It has not been coloured, only a bold brushstroke has stained its surface with orange-red ink. A framed 2.5 guilder coin pinned to its corner shows us the silver profile of Merchant King William I.

A monumental Javanese Hornbill dominates the stage in Korver’s fifth painting De Handel Mij (the Trade Company). Here the floor is filled with pieces of broken Delftware, a typical pewter chocolate kettle and some silver moulds for chocolate eggs. The delicate bars of this aviary display the facade of Herengracht 40 against the background of an Indonesian landscape. This aviary is sealed, however; only very small birds - and mice – are able to amble in and out. The glorious economic recovery the Netherlands enjoyed during the 19th century owes much to the activities of the NHM during its years at Herengracht 40. They were the years when the so called Colonial Gains more than once ran up to over 30% of the national budget; they were also the years of enormous limitations put upon the freedom of other peoples in other places overseas. The NHM, King William I’s attempt to revive the glory days of the Dutch East India Company, would eventually evolve into today’s ABN-AMRO bank. But in the mid 19th century it found itself the target of what is most likely the fiercest “I accuse” in Dutch literary history: Max Havelaar, the famous novel by Multatuli.

.

"The entrance seems to have gained a very special and subtle warmth ever since these birds have been installed here."

And so this series of images in the entrance not only makes an historical loop that places this house in a larger historical process, at the same time the role of the cages appears to have come full circle also. While the first three paintings deal with the psychology of the caged unable to see or accept the doors of their aviary to be in fact open, and the opened front of Amsterdam city hall in Hôtel de Ville was stretched to theatrical proportions, the mid 19th century economic recovery of the Netherlands was largely based on the incagement or sheer confinement of the other.

To the owners of Herengracht 40 all this is of no daily concern. As the lady of the house puts it: ‘I just enjoy the wonderful splendour of all these birds every time we come home. The entrance seems to have gained a very special and subtle warmth ever since they’ve been here.’

And this was exactly Korver’s aim. ‘It is not my place to make any moral judgment on history’s reality, that’s just too easy and it doesn’t change anything; furthermore, it wouldn’t be healthy for the house itself, I guess. I just wanted to bring all this history to the surface and embed it in something very beautiful.’

.