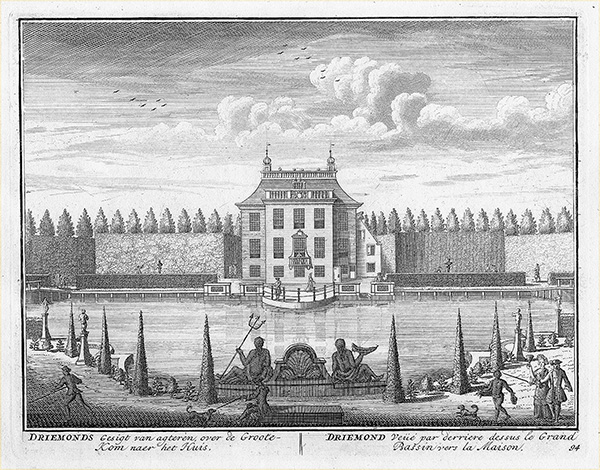

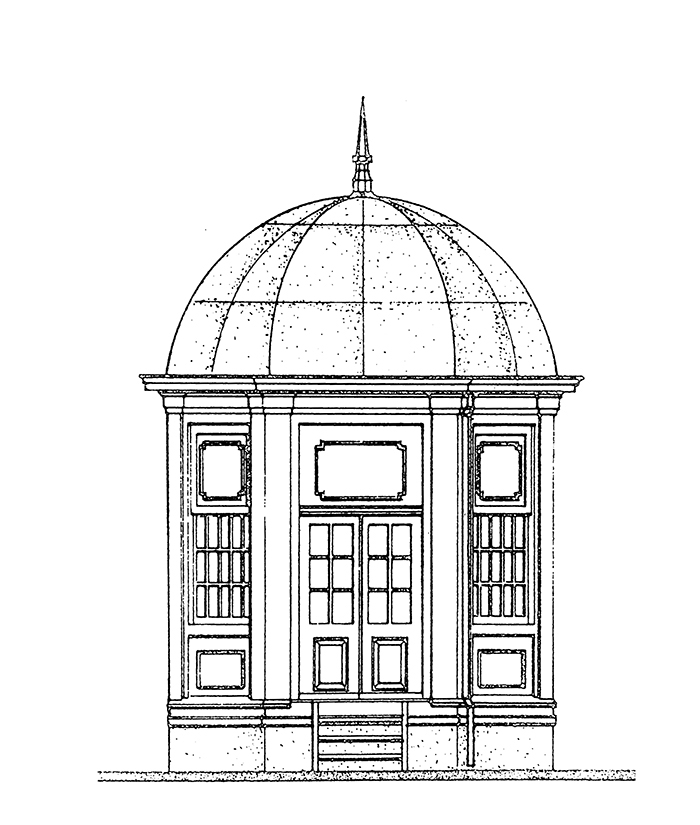

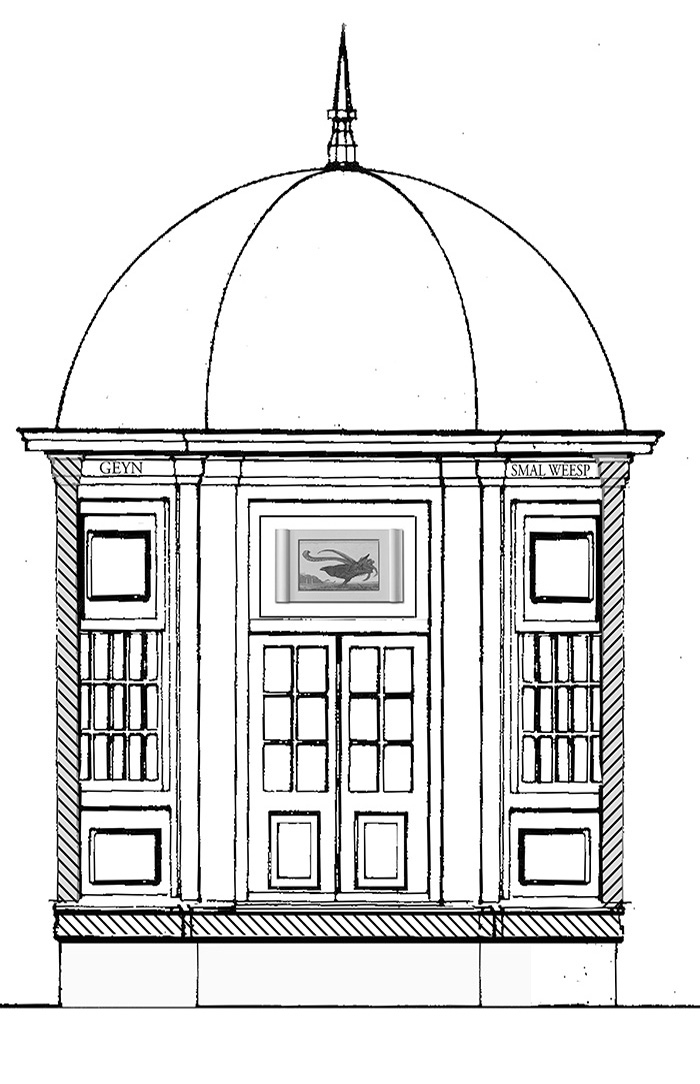

A new painted ceiling and four "overdoor" panels, all for a Louis XVI Tea-pavilion, last remaining relic of two demolished 17th-century country estates and a menagerie portrayed by Hondecoeter. . .

Photography; Eddy Wenting.

Alte Pinakothek Museum - Munich.

Somewhere at the beginning of the 19th century, the pavilion was moved a few hundred meters away from its original spot between the road and the river, and so more or less became part of the menagerie of the original house “Schoonoord”.

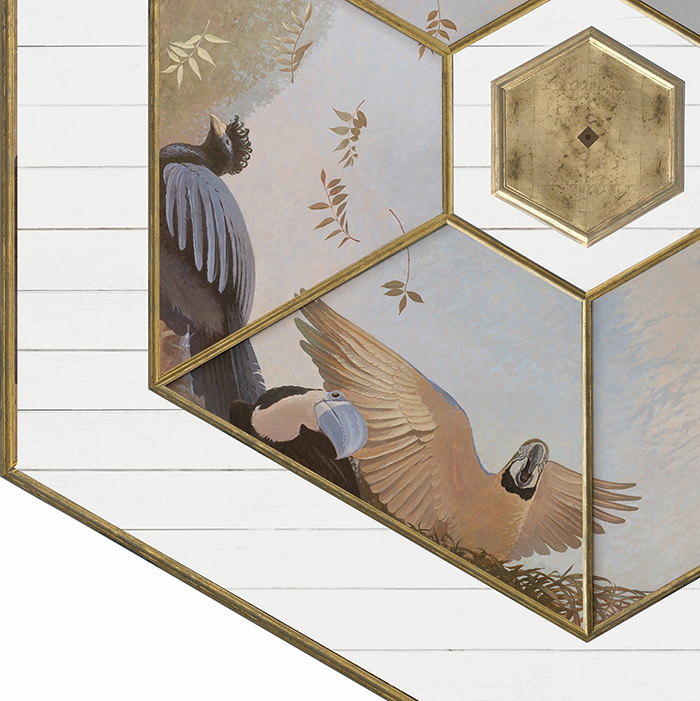

Since tea domes often also show a formal relatedness with bird cages, it seemed appropriate to take the animals in Dutch 17th and 18th c. menageries as point of departure for a new ceiling painting in this historic building.

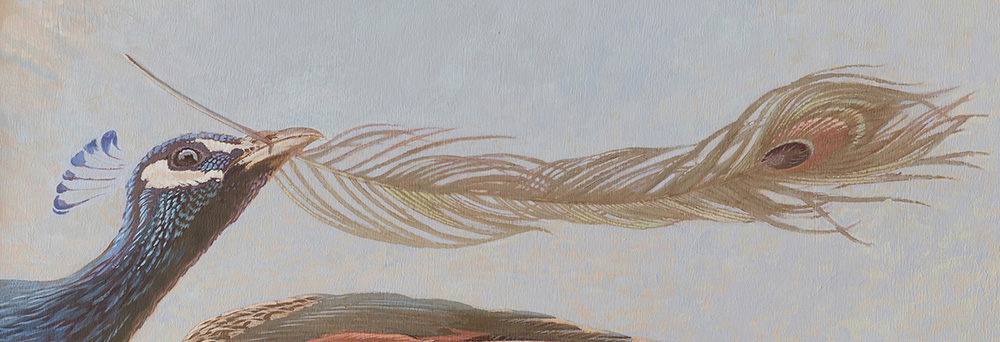

A well-known 1708 Abraham Busschop ceiling painting in the collection of the Dordrecht museum, shows a raven being robbed of the found and stolen feathers he has adorned himself with. During the design process a peacock borrowed from this work kept popping up in the collages and drawings that arose. "In the end I accepted his presence," says Korver, "and included the animal as a quote in the new work. Something traditionally known as ‘schilderkunstige onleening’ or painterly appropriation.”

Interestingly this borrowed bird by Busschop brought about a shift in the image’s meaning, making it fit into a long tradition of fable paintings. Ravens with stolen feathers, admonishing against showing off with wealth, achievements, properties or ideas that have been appropriated dishonestly.

the dandylion ( Taraxacum officinale ) seems to mimic the birds tail.

.

East- and West India company vessels used to take wild animals as an extra on their months long journey back home. Although the chances of survival were minimal, there was an insatiable market waiting in Amsterdam.

The new ceiling shows us an array of birds known to have been present in 17th-century Holland. They have been grouped in roughly three clusters representing their place of origin in South East Asia and Latin America.

November 2020

.

Tempera, Acrylics and goldleaf on wood - diameter 405 cm

.

Cosmopolitan urban dwellers in a globalized world.

.

.

.

a bird brought over on a VOC vessel, most likely from Sri Lanka ( Ceylon)

.

.

Ravens

.

.

The Dutch acquired and accumulated their wealth mostly by trade but often also through the violence and brutal atrocities that so often accompany a position of maritime and military dominance. Yet, where the main character of numerous Dutch bird paintings and ceilings, the Raven from the fables of Aesop and la Fontaine, in the end received a beating for its dishonest behaviour towards the other birds, thus conveying its virtuous and admonishing message to us, in reality the display of Hollands accumulated wealth went mostly unchallenged.

RAVENS

Ravens were also added to this tea pavilion by Korver, on a set of new “Supraporte” paintings above the windows and the door. In this setting these birds can show their acquired feathers undisturbed. Posing with great confidence, clearly outlined against an empty sky over a low horizon.

.

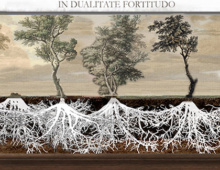

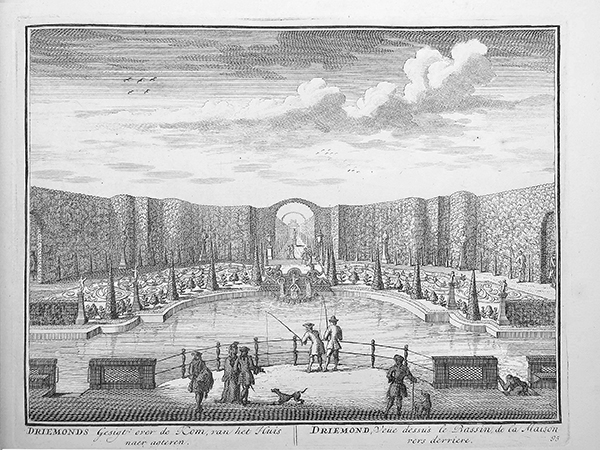

Hondecoeter painted Driemond House and its exotic fowl against the background of an idealized Italian landscape. These ravens however, are set in a Dutch polder, with historic details appearing in the background, like set pieces on a theatre stage; the surviving 18th-century gateway of Schoonoord House, the tea pavilion itself and the facade of House Driemond as we know it from Stoopendaals engravings and the Hondecoeter painting. One of the paintings shows a windmill on the distant horizon, seemingly an ironic detail of an overexploited icon of Holland. It is the "Broekzijder" windmill, built along the Gein river in 1641 - and still there today – draining these lands, thereby enabling Driemond House to be built in the first place, and these ravens to keep dry feet.

A technical facility as a small detail far off in the distance, enabling the theatre in the front to take place.

.

.

Acrylics and tempera on Aluminum.

.

Acrylics and tempera on Aluminum.

.

Acrylics and tempera on Aluminum.

.

Acrylics and tempera on Aluminum.

.

What we can relate to however, according to Korver, is the story of the individual animal that was captured one day somewhere in 17th c. Batavia, Ceylon or Suriname, appropriated, sold, and after surviving a sometimes yearlong sea voyage, spent its later days as an ornament in a menagerie of a rich and refined country estate somewhere in the marshlands around 17th century Amsterdam.

“I recently met a young Nigerian women studying international relations in Rotterdam while living in Amsterdam as an au pair,” says Korver. “Seeing this work she sighed and summarized it concisely; "In the end it's just like slavery isn't it?". . . "Just the same as any other form of appropriation, back then just as well as today. Turning the body of “the Other” into an object with just one simple sentence;

I like that body ... I'll have it."

.

1) Inspired by the zoo Louis XIV had ordered to be built at Versailles, menageries enjoyed great popularity all through the 17th- and 18th-century. Within the city of Amsterdam at least two could be visited, but at the numerous country estates outside the city walls menageries were regarded a standard garden accessory for the exceptionally well-to-do. Famous for its rich collection of animals from all over the world was the Menagerie of “Stadhouder“ Willem V at the palace in Voorburg.

2) Paintings, panels and ceilings depicting domestic and exotic birds were in high demand. It seems Adolf Visscher and Anna Maria Pelt, new owners acquiring Driemond House in 1671 had a rich collection embellishing the walls of their Amsterdam canal palazzo and the Driemond estate, among them fifty works by Hondecoeter alone. Paintings like these were not just a colourful display of painterly virtuoso; these birds were seen as a reflection of the owners wealth and the international power of the Dutch republic.

Study for a preview exhibition before final installation of the work.

.

.

.

.

.

The Pinnate leaves of a European Ash bring to mind the appropriated feathers in Aesop’s and la Fontaine’s raven fable.

.

.

Photo; Korver - Nov. 2020

.

.

Photo; Korver - May.

.