"I AM A BIOLOGIST AT HEART"

The natural world has fascinated Dutch painter Peter Korver since his earliest childhood, but the road to finding a way of expressing his great affection was hardly linear. Yet instead of regretting the detours he took, Korver now uses his background in biology, history and art to create wall and ceiling paintings that not only celebrate the natural world but are also rich in historical meaning. As an artist specialized in paintings depicting delicate images of flora and fauna; be it butterflies, tropical birds, feathers, snails or wheat, Korver strings all ingredients together using historical and monumental interiors as his canvas. We visited him in his Amsterdam studio where the arts of painting and story-telling get blended into a poetry of nature . . .

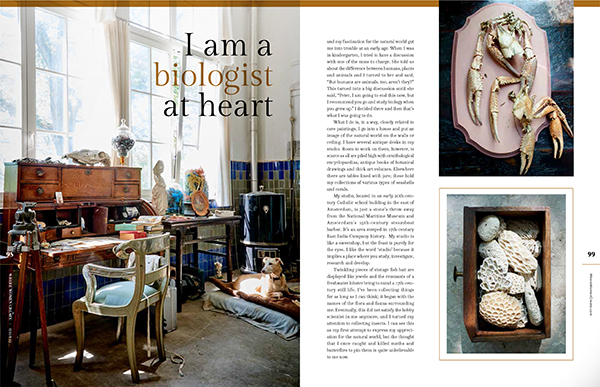

“Basically I am still a biologist at heart, with a fascination for the natural world that got me into “trouble” at a very early age. I remember in kindergarten trying to have a discussion with one of the nuns in charge. She told us about the difference between humans, plants and animals so I turned to her and said, “But humans are animals, too, aren’t they?” This turned into a big and unpleasant discussion until she said “Peter, I am going to end this now, but I suggest you go and study biology when you grow up, and do something about it yourself” I decided there and then that’s what I was going to do.”

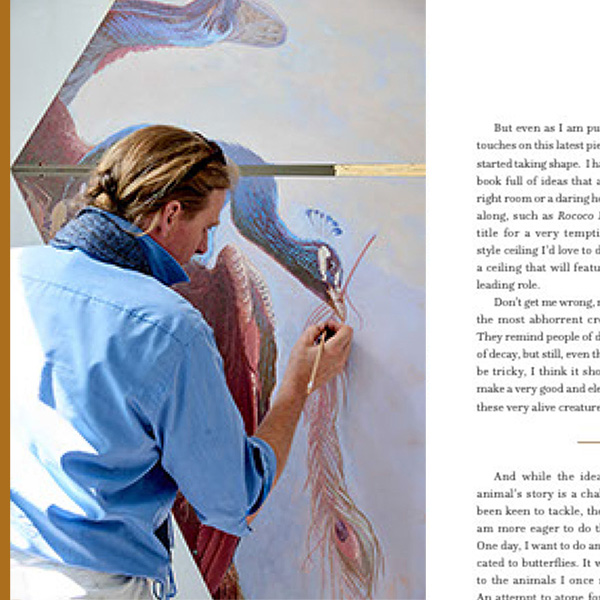

"What I do these days is, in a way, closely related to cave paintings; I go into a house and put an image of the natural world on the walls or ceiling."

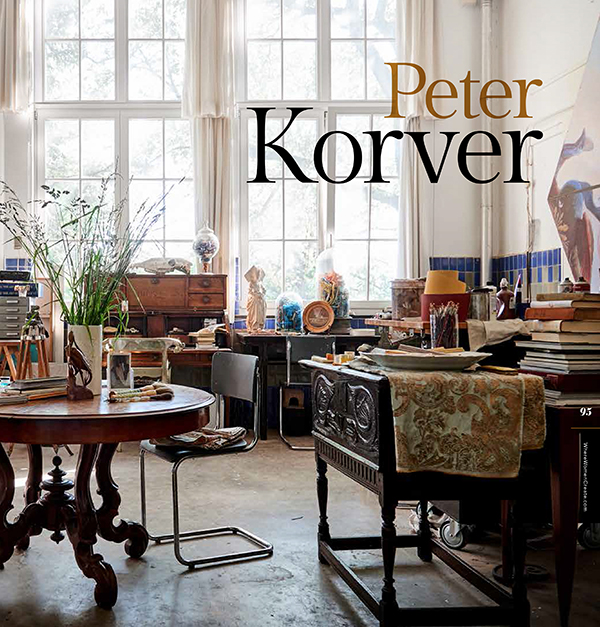

“I like the word ‘studio’ because it implies a place where you study, investigate, research and develop.”

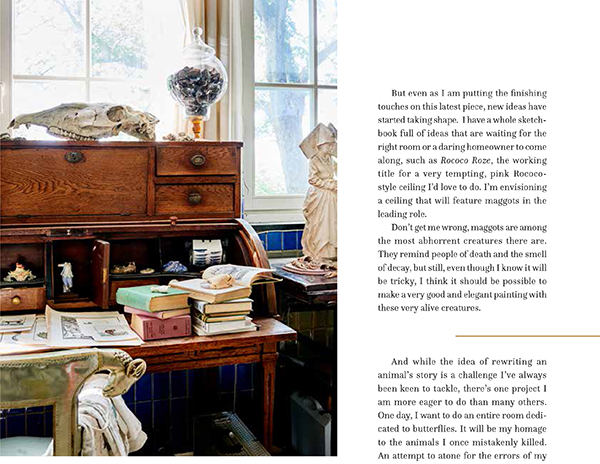

Korver’s studio, located in an early 20th-century Catholic school building in the east of Amsterdam, is just a stone’s throw away from the National Maritime Museum and Amsterdam’s 19th-century steamboat harbor. It’s an area steeped in 17th-century East India Company history

The space is like a sweetshop, but the feast is purely for the eyes. Twinkling pieces of vintage fish bait are displayed like jewels and the remnants of a freshwater lobster bring to mind a 17th-century still life.

“I have several antique desks in my studio, but", he pauses smiling, "room to work on them can be a little scarce at times,” And indeed most desks are piled high with ornithological encyclopedias, antique books of botanical drawings and thick art volumes. Elsewhere there are tables lined with jars, these hold parts of his extensive collection of seashells.

“I’ve been collecting things for as long as I can think; it began with the names of the flora and fauna surrounding me. Eventually, this did not satisfy the boy-scientist in me anymore, and I turned my attention to collecting insects. I can see this as my first attempt to express my appreciation for the natural world, but the thought that I once caught and killed moths and butterflies to pin them is quite unbelievable to me now.”

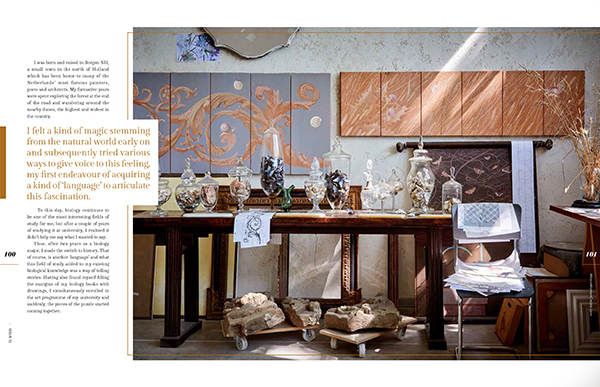

Born and raised in Bergen NH, a small coastal town in the north of Holland which has been home to many famous Dutch painters, poets and architects, his formative years were spent exploring the forest at the end of the road and wandering around the nearby dunes, the highest and widest in the country.

“I felt a kind of magic stemming from the natural world early on and subsequently tried various ways to give voice to this feeling, my first endeavour of acquiring a kind of ‘language’ to articulate this fascination.”

“To this day, biology continues to be one of the most interesting fields of study for me, but after a couple of years of studying it at university, I realized it didn’t help me say what I wanted to say. Thus, after two years as a biology-major, I made the switch to history. “That of course, is another ‘language’ and what this field of study added to my existing biological knowledge was a way of telling stories. Having also found myself filling the margins of my biology books with drawings, I simultaneously enrolled in the art program of my university and suddenly, some pieces of the puzzle started coming together. Later, after working a few years as a painting assistant for Jan Beutener, one of the more influential artists and art educators at that time, I subsequently got invited to do the design of some restaurant and home interiors. That's where the first animals appeared on the walls, and from there on there was simply no going back.”

“I think all of these paths I explored were about trying to find a way of coping with the idea that I found something unbelievably beautiful. What I love so much about the form of expression I have ultimately found is that, if you paint an animal, you can change the way people perceive it. . .

A prime example of this are the moths he began collecting as a boy, which continue to find their way into his work. “Moths are often connected with bad omens and other obscure stuff like wandering souls; and yet, they are first and foremost independent animals, very much alive and often stunningly beautiful.”

One of his latest works, the painted walls and ceiling in the Grand Salon of the 17th century Presidential Palace in Malta, has thus come to feature a loose gathering of four closely related species of Mediterranean hawk-moths. “One evening, while on a research trip during which I stayed at the palace, I walked back over the gallery overlooking the gardens. It was just before nightfall and suddenly a big insect passed me by. The size, the sound, the silhouette and the time of day: this was unmistakably a hawk-moth, one of my favourite animals since childhood.”

Shortly after this encounter he decided to use these animals in the paintings for the Salon. “A resting hawk-moth has a very specific triangular shape, and four of them pointed towards each other subtly seemed to resemble the shape of a Maltese cross. It really pleased me having been able to connect the two.”

"You can disconnect it from very strong, symbolic meanings and after having thus unhinged it from such existing connotations, find brand new ways of telling stories with it."

A prime example of this are the moths he began collecting as a boy, which continue to find their way into his work. “Moths are often connected with bad omens and other obscure stuff like wandering souls; and yet, they are first and foremost independent animals, very much alive and often stunningly beautiful.”

One of his latest works, the painted walls and ceiling in the Grand Salon of the 17th century Presidential Palace in Malta, has thus come to feature a loose gathering of four closely related species of Mediterranean hawk-moths. “One evening, while on a research trip during which I stayed at the palace, I walked back over the gallery overlooking the gardens. It was just before nightfall and suddenly a big insect passed me by. The size, the sound, the silhouette and the time of day: this was unmistakably a hawk-moth, one of my favourite animals since childhood.”

Shortly after this encounter he decided to use these animals in the paintings for the Salon. “A resting hawk-moth has a very specific triangular shape, and four of them pointed towards each other subtly seemed to resemble the shape of a Maltese cross. It really pleased me having been able to connect the two.”

Korver mostly works with tempera and acrylics, but has also used materials such as ground Maltese limestone to give his work yet another layer of meaning and a sense of place. Before starting the paintings for the San Anton Palace in Malta, he spent some time on the islands; “Straight after my arrival I walked out of the urban area and over the rocks along the coast heading north, when at some point I peeked into the quiet water and saw sea urchins crawling slowly over the bottom. Then I noticed the same animals all around me in the limestone rocks, fossilized millions of years ago. This gave me an overwhelming feeling of continuity, which would later lead me to develop a paint using fine pulverized Maltese limestone.” This was used as the background colour in his paintings that now adorn the six-meter-high walls of the palace’s Grand Salon.

Most viewers probably don’t notice all the carefully constructed elements and considerations that come with each piece, but that hardly bothers him. "I think these cultural, biological and historical details and references function on a subconscious level. They are part of the building structure of the image just as much as the quality of the brush strokes or the rhythm of the composition."

"Each of these elements adds energy to the painting, and taken all together they make up the richness of the finial work."

Having recently completed his Maltese project, Korver turned his attention once again to “Other One’s Feathers”, a painting he began in 2017. When finished, it will be fitted into the hexagonal ceiling of an 18th-century tea pavilion–a last remaining piece of architectural history, formerly belonging to two 17th-century mansions that, in their heyday, had been the crown jewel of the Dutch town of Driemond but have sadly since been demolished. Once surrounded by majestic baroque gardens with ornamental lakes, these estates would have included several menageries featuring a large selection of tropical birds brought to the Netherlands by the Dutch East- and West India Company. “Mind you, these birds in Driemond have at the time actually been portrayed by Hondecoeter, Holland’s most important bird painter of the 17th century, and can still be seen today on a set of room sized paintings on display in the Rembrandt room of the Alte Pinakothek Museum in Munich.”

Historical research has shown that all birds I chose to depict in this painting could have been found in menageries in and around Amsterdam at that time. The funny thing is that, one day I stepped back from the painting and realized that they had ordered themselves according to their places of origin in Latin America and South-East Asia.”

Historical research has shown that all birds I chose to depict in this painting could have been found in menageries in and around Amsterdam at that time. The funny thing is that, one day I stepped back from the painting and realized that they had ordered themselves according to their places of origin in Latin America and South-East Asia.”

"Moments like that, when things come together almost without my doing, can really move me; they can feel almost like magic."

“Other One’s Feathers" is a provisional title by the way, it's derived from Aesop's fables, rewritten by LaFontaine in the 1660's and extremely popular until late in the 18th century. This story revolves around a raven that has dressed himself in beautiful feathers that are not his own. Donning this new outfit, he goes to the king to show off his magnificent plumage, only to get a beating from the birds whose feathers he had robbed. There are quite a lot of images of this scene dating back to the 17th century and the morality, of course, is that you don’t show off with stuff that’s not yours. However, while the Dutch would adorn their ceilings with these paintings, thereby professing to their morality, on a daily basis they would of course do the exact opposite, ripping off their colonial subjects and show off with their acquisitions. So, this painting is basically about the birds that in reality never got their feathers back.”

Still playing around with some ideas for this work, Korver recently decided to include some paintings of ravens above the doors of the historic tea-pavilion. This somehow seems to introduce himself into the work; "Latin for raven is Corvus, a word closely related to my family-name. I’ve decided these will be some very self-assured ravens, with lots of ‘other one’s feathers’ in their butt. Not only as a subtle reference to the never returned Dutch colonial gains but also ironically hinting at all this history and monumental buildings I tend to dress myself and my paintings with.”

But even as he is putting the finishing touches on this latest piece, new ideas have already started taking shape. “I have a whole sketchbook full of ideas that are waiting for the right room or a daring homeowner to come along, such as Rococo Roze, the working title for a very tempting, pink Rococo-style ceiling I’d love to do, a ceiling featuring maggots in the leading role. Don’t get me wrong, maggots are among the most abhorrent creatures. They remind people of death and the smell of decay, but still, even though I know it will be tricky, I think it should be possible to make a very good and elegant painting with these very alive creatures.”

And while the idea of rewriting an animal’s story is a challenge he has always been keen to tackle, there’s one project he is more eager to do than many others. “One day, I want to do an entire room dedicated to butterflies and moths. It will be my homage to the animals I once mistakenly killed.” Keen to experiment in the early stages of a project, Korver has painted butterflies on slates, testing his designs on this very natural and rough material. “These days I find it rather oxymoronic that butterflies are often used to symbolize aliveness, spring, joy and vividness and yet, the image of butterflies depicted in that kind of context is most of the time a dead, pinned and dried one. The idea for the room would be about something that is so beautiful, you want to keep it, but in order to keep it, you would have to kill it.”

Still playing around with some ideas for this work, Korver recently decided to include some paintings of ravens above the doors of the historic tea-pavilion. This somehow seems to introduce himself into the work; "Latin for raven is Corvus, a word closely related to my family-name. I’ve decided these will be some very self-assured ravens, with lots of ‘other one’s feathers’ in their butt. Not only as a subtle reference to the never returned Dutch colonial gains but also ironically hinting at all this history and monumental buildings I tend to dress myself and my paintings with.”

But even as he is putting the finishing touches on this latest piece, new ideas have already started taking shape. “I have a whole sketchbook full of ideas that are waiting for the right room or a daring homeowner to come along, such as Rococo Roze, the working title for a very tempting, pink Rococo-style ceiling I’d love to do, a ceiling featuring maggots in the leading role. Don’t get me wrong, maggots are among the most abhorrent creatures. They remind people of death and the smell of decay, but still, even though I know it will be tricky, I think it should be possible to make a very good and elegant painting with these very alive creatures.”

And while the idea of rewriting an animal’s story is a challenge he has always been keen to tackle, there’s one project he is more eager to do than many others. “One day, I want to do an entire room dedicated to butterflies and moths. It will be my homage to the animals I once mistakenly killed.” Keen to experiment in the early stages of a project, Korver has painted butterflies on slates, testing his designs on this very natural and rough material. “These days I find it rather oxymoronic that butterflies are often used to symbolize aliveness, spring, joy and vividness and yet, the image of butterflies depicted in that kind of context is most of the time a dead, pinned and dried one. The idea for the room would be about something that is so beautiful, you want to keep it, but in order to keep it, you would have to kill it.”